- Home

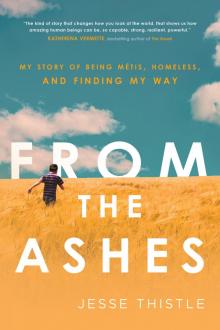

- Jesse Thistle

From the Ashes Page 2

From the Ashes Read online

Page 2

“But, Blanche,” Kokum said, “we’ve picked berries for the bannock.”

“Can’t,” Mom said. “Sonny needs to get back. Damn idiot’s gotta meet someone. Come, boys, hurry it up.”

My mother was just fifteen when she met my father in 1973 at her sister Bernadette’s house in Debden, Saskatchewan. According to my aunties, my mother was just about the prettiest Native girl in all northern Saskatchewan—a Michif Audrey Hepburn crossed with Grace Kelly and Hedy Lamarr. Silken black hair down to her waist, jet-black eyes, and a smile like a midnight flame. They said men hovered around her like moths, and that when Dad first laid eyes on her, he tripped all over himself to catch her. He chatted her up, bought her stuff, and fawned over her. He looked like a bumbling fool, my aunties said, all the men did.

But Dad was different. He was an Algonquin-Scot, although my uncles tell me he knew himself as a white man. He wasn’t much to look at—chubby around the middle, with a pockmarked face and broken fighter’s teeth, and his usual jean outfit was slick with traveller’s patina. But there was something charming about him, an ability to talk and a boldness. That apparently came from his rough blue-collar upbringing north of Toronto, where he learned to hustle or perish. He also loved rock music. Deep Purple, Foghat, Jethro Tull, Black Sabbath, Johnny and Edgar Winter—he knew all their songs and more, how they were written and the stories behind their creation.

My mother, Blanche Morrissette, and father, Cyril “Sonny” Thistle, in 1977 in Debden, Saskatchewan.

Mom was stuck in the 1950s, listening to old country music—the Carter Family, Patsy Cline, Hank Williams, Bill Monroe, Don Messer, anyone of the sort. She did know some modern music—Bob Dylan, the Doors, the Guess Who, Joni Mitchell—but she couldn’t match my father. My aunties said Mom told them Dad was like a jukebox, with info on all the hottest bands. That made him like a god in northern Saskatchewan, where no one knew anything about rock, or Led Zeppelin, or Jimi Hendrix, or anything.

It made him irresistible, Mom said.

The side of my mom’s face was blue. It wasn’t that way before she left. And her voice sounded the way I didn’t like. Mushoom examined her, and I knew he could see her broken glasses sticking out of her pocket when she went into the back room. He pushed himself up from the table, swore, and reached for his axe.

I thought he was going to kill my dad. Josh, Jerry, and I all started crying.

“Stop, Jeremie,” Kokum yelled. She pulled the axe out of his hand and threw it beside the stove. “This is between them,” she said, her voice sounding the way it had when she spoke with the mosquitoes.

Mushoom sneered, then stared out the window. Dad didn’t notice. I could see him drumming his hands against the steering wheel.

Mom came back with some things. “Sorry, Mom, Dad. Next time we’ll stay for bannock.” She picked up our toys, then piled us into the car. She was like a whirlwind—we didn’t even have a chance to say goodbye. As soon as we were in the car, Dad floored it. The wheels kicked up a cloud of dirt, and I could just see my kokum and mushoom waving to us through it.

HORNET

DAD BURST THROUGH THE APARTMENT door, his dirty-blond mullet in full flight. He was grinning so widely his greasy handlebar moustache splayed out at both ends. In his hands were a coffee tin and a white plastic bag.

“Daddy got paid, boys!” He placed his bounty on the cardboard box that served as our coffee table, then fell backward onto the sofa. A plume of sour dust erupted from the cushions. The tin rattled, and a nickel spilled out over the edge and rolled a foot or two toward us.

When Dad opened his arms for a hug, Josh ran from his usual spot in front of the TV and grabbed his legs. Jerry and I were still watching television—a shark attacking an octopus on The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau. A red cloud of ink filled the ocean water. As the octopus scurried to safety, we joined Josh and hugged Dad.

“I did what you said,” Josh said. He still clung to Dad’s jeans. “I kept an eye out and made sure no one came in the apartment while you were gone.”

Josh was in charge of Jerry and me whenever Dad left us alone to go on a mission. He was five.

“Make sure to feed your brothers,” Dad would say. “Don’t let no one in. Hide in the vent behind your bed if anyone gets in. And don’t turn the light on at night because they’ll know you’re inside. Got it?” Josh always nodded.

Even four-year-old Jerry was my boss. We were like a little tribe with Josh as our chief, Jerry as second-in-command, and me as the expendable warrior. I had to do the bidding of both. They made me stand on the chair to check the peephole when someone was at the door. They made me fish poo out of the toilet to smear on walls to get even with Dad for leaving us alone. And they always made me climb onto the counter to reach where Dad hid all the best food away in the top cupboard. It was dangerous to climb so high, but I was good, and I was never afraid of heights like Jerry and Josh were. Climbing came naturally, and the distance between me and the floor excited me and made me feel powerful—it was something my brothers couldn’t do.

Dad would freak out when he found that we’d eaten his secret food—cans of Spam, peanut butter, loaves of bread, chips, and the odd jar of Cheez Whiz—which he never shared, and I always got the blame because I never talked, even when I played alone with my brothers, and even when I got a licking. Mom used to think I was mute, but I could speak fine, I just chose not to. My words belonged to me, they were the only thing I had that were mine, and I didn’t trust anyone enough to share them.

Dad was only gone for a night this time, but in the kitchen, the cupboards only had a few unopened cans of beans and beets he’d gotten from the local food bank a few days before. Empty boxes of crackers and cans piled one on top of another, covering the countertops and cascading out over the stovetop. The fridge had a few half-drunk beer bottles, an old light bulb, and a hardened turnip. Sometimes he’d go away for two or three days and leave us nothing.

“Good boy.” Dad rubbed Josh’s head, then pushed the three of us off of him. Josh, Jerry, and I fell to the beer-stained carpet, like puppies bucked off their mom’s teat, as Dad cradled his bag.

My mother had abandoned my father, my brothers, and me—that was the version of the story we were made to believe by my father’s family. But it wasn’t the whole picture.

Mom married Dad when she was just seventeen, and my father was twenty-two.

She gave him an ultimatum the day of their wedding: “Quit drinking and running around, or I’ll leave you.”

He promised her a life of sobriety.

Dad lasted three days before he drank himself into a stupor.

One day he took his anger out on everyone. Josh endured a beating and Mom received it even worse.

Mom had had enough of moving from apartment to apartment, room to room, of my dad wasting all the money and opportunity that came their way. She’d had enough of all the bullshit. She packed our bags while Dad was passed out on the couch, and the four of us moved to Moose Jaw.

YVONNE RICHER

My brothers, Jerry (on the left) and Josh (in the middle), and me (on the right) in 1979 in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan. Our aunt Yvonne, my mother’s sister, took this picture.

Mom went to night school and began working at a local restaurant during the day. Life was steady—we stayed in one apartment, slept in beds instead of on piles of laundry, and ate frequent meals, and Mom didn’t cry herself to sleep with bruises like before.

One day Dad showed up.

He was healthy, coherent, and his clothes were clean. He charmed his way through the front door, telling Mom he’d found a great job back east with his father, that he wasn’t drinking and drugging, and that he’d found an apartment and could afford to keep us boys if she allowed us to go with him. He wasn’t trying to get back with her—he knew not to go there.

“I’ll return them after a few months. You have my word, Blanche.”

I think Mom decided to let us go with Dad because she wasn’t thi

nking straight—she was exhausted—and Dad knew how to sound convincing when he wanted something and could exploit Mom’s weaknesses. He had skills from years and years of hustling.

Mom let us go. I could smell the pine scent in her hair as we hugged goodbye on the veranda.

I didn’t blame her. Dad could sell the Brooklyn Bridge to New York City officials if he really wanted to, or so people said. He was just that good at lying.

“Look here,” Dad said as he broke open the bag and an avalanche of cigarette butts spilled onto the floor. He grabbed my brother’s arm and placed him in front of the butts beside the TV. “Jerry, you roll the best. Take my Zig-Zags and do like last time.”

Jerry peeled out a rolling paper and set to work ripping open the largest butts onto a sheet of paper. The smell of mouldy smokes filled the apartment. Dad then poured the contents of the tin onto the carpet. The coins were like falling treasure and Dad looked like a pirate, like Captain Hook in the Peter Pan book Mom used to read us before bed.

“Josh, count ’em up,” he said. “Jesse knows what pennies are. Just let him pick them out before you get started.”

Josh nodded and got my attention. “Like last time, Jesse. Remember?” He held up a penny and told me to dig. I shoved my hand in the pile and began picking out what looked to me like nuggets of gold.

“Dad,” Josh said before we got too far. “We haven’t eaten since yesterday morning and it’s nighttime now. We’re hungry. Did you bring anything?”

“Shit. I forgot. Count it up. We’ll go to the store and get something after. Promise.”

I watched as he pulled a small Baggie filled with white powder out of his jean jacket pocket. He held it up to the light and flicked it, then made his way to the washroom and slammed the door.

Josh sighed and began helping me. My stomach gurgled. He looked over at me. It was Josh’s job to feed us. Sometimes he’d leave Jerry and me alone for a while and walk to the convenience store to beg for money to buy food. We’d seen Dad do it and knew how to do it, too. It usually took Josh a couple of hours, but he always came back with chips and pop and other goodies. He was my hero, my chief!

Sometimes, when we got really hungry, Josh even took Jerry and me over to ask for change in front of the hockey arena around the block. It was the best spot because we could buy gigantic hot dogs there. We shared bites. The hot meat burst with such flavour that my jaw would ache up around my ears, and my tongue swam in pools of saliva. Drool would sometimes spill out of my mouth onto my shirt before I even took a bite.

Dad’s treasure shimmered in front of the TV. The wildlife program was still playing, and a whale drifted through blue water, calmly scooping mouthfuls of food, as Josh and I rifled through the silver and gold pile, and images of those hot dogs piled high with ketchup and mustard and relish and everything else floated through my head.

I noticed light peeping out of the washroom. Dad must’ve slammed the door so hard it bounced open a crack. I dropped the gold pennies I had in my hand and crawled over quietly to see what he was doing. Josh trailed behind.

Dad was on the toilet, hunched over with a spoon in one hand, a blue lighter in the other. Red flame licked the bottom of the spoon and bubbles spit droplets into the air. Dad’s forehead was wet, sweat dripped onto the tile floor, and that see-through thingy I’d found one day underneath the sofa was by his side.

Dad had told me it was a man-made hornet, and that kids shouldn’t play with it because they’d end up getting stung by accident, and the medicine it carried could make young boys so sick they could die. The black stripes on its see-through body looked scary, like the blue-and-black hornets I saw flying in the prairie roses, the kind that stung me when I went to see Kokum Nancy.

Dad picked up the hornet, put it near the spoon, and it sucked the medicine into its belly. Then he wrapped his leather belt around his arm and held one end in his teeth, pulling back with his head like my uncle Paul’s dog did whenever we played tug of war. I could see green veins on his arm and hand. He jabbed himself with the hornet and red shot into the hornet’s body. I pushed my face right up against the crack trying to get a better look, as bad butterflies swam all through my guts.

It looks just like the red ink that the octopus shot into the ocean right before it escaped the shark, I thought. I wondered if my dad could run away, or if a shark would get him. The softness of Kokum’s voice whispered in my ears, as the smell of sweet Saskatoon berries filled my nose. The butterflies flew up my body and out the top of my head.

Dad let go of the belt, moaned, and toppled off the edge of the toilet. I pushed the door open and ran to him. He didn’t move, and his eyes were closed. I looked back at Josh. He stood in the arch of the doorway, a dark river spreading down the front of his brown corduroys.

TRASH PANDAS

THE PINK NEON SIGN ON the corner store drooped down to one side and flickered off and on. The light strobed against the window I was standing in front of, staring at the huge ice-cream cone on the advertisement taped against the inside of the glass.

“Jesse, pay attention,” Dad said and pushed my shoulder. Blankets of dead leaves swirled alongside the building when the wind picked up, and Dad tucked his head into the collar of his jean jacket. I saw an old man wearing a hat approach from the path over near the grass. Dad headed him off by the corner. I tried to focus.

“Excuse me, sir,” Dad said. “I was wondering if you had some spare change? I got three kids, and they haven’t eaten today.” Dad sounded polite as he motioned over at us, and we stood, hands out, with big eyes, just like Dad taught us. “We’d really appreciate anything.”

The man peeled his trench coat open, searched his pockets, and shrugged. “Sorry, fella. Don’t have change to spare.” He moved past us and entered the store. The entrance bell rang—it was a sound that meant defeat and more begging. I watched through the window as he bought milk and bread. He got some change back. When he came out, I ran over and tugged his leg, trying to make his quarters and dimes jingle in his pocket, to let him know I knew he had change. He kicked me away. “You should be ashamed,” he said to my dad.

“Fuck you,” Dad fired back and flicked his cigarette in the man’s direction. Dad was shivering. Josh sighed, and Jerry wrapped his arms around Josh in a bear hug and squeezed until Josh laughed and begged him to stop. Dad was busy searching the sidewalk and found a half-smoked butt near a trash bin.

“I’m not eating out of there again,” Josh said, his eyes focused on my father and the bin. He kicked the wall. “We’re not supposed to.”

Dad put the butt in his mouth and lifted the lid off the garbage container. “You never know what you’ll find.”

He was right. A couple of days ago, when Dad had taken off, Josh took Jerry, leaving me in the apartment. I’d watched out of our window and could see Jerry as he made a beeline toward the bin, climbed up, and dove into the pool of black trash bags. He looked like a raccoon. After a few minutes, he emerged clutching some old bread, a couple of packs of cold cuts, and a few dented cans. He tossed them to Josh, but Josh fumbled and dropped them like an outfielder having a bad day. The bread and meat were still good, just a little green around the edges. When we picked that off though, it was as good as new.

“Nothing in here, boys. Pickup was last night.” Dad shut the bin lid and pulled his collar up. His cigarette went out. The November wind bit through our clothing, and we huddled together. We’d been out for a few hours and hadn’t come up with any change. Everyone seemed to be in a rush or didn’t have enough to spare. We always shared what we had, and I didn’t understand why people were so mean and wouldn’t share with us.

“Listen,” Dad said, “I have a plan.” He knelt down in front of Jerry and Josh, placing his hands upon their shoulders. “I’ve done it with Josh before, but we’re all here today, so I think it’ll work better.”

Josh perked up, but Dad didn’t even glance at me. I stuck my tongue out.

“Now, now. You’re only three, bu

t you can help, too, Jesse.” Dad patted my bum. “Josh knows the drill. Just follow behind him and do what he says.”

Josh put his arms around Jerry and me and pulled us close. “Just stay beside me and run when I tell you,” he whispered. “Go straight back to the apartment and don’t follow Dad!”

Dad winked at Josh. “That’s right, son.”

I was so jealous of Josh.

I held on to Josh’s sleeve when we entered the store. Jerry was right beside me ogling the rows of chips and candy. The storekeeper looked down at us but then fixed his eyes on Dad, who walked ahead, leaving us behind. Before I knew it, he was by the milk and pop near the back of the store. His head darted around—down at the floor, over to the chocolate bars, up to the lights—like he didn’t know what he was looking for. Inch by inch, Josh nudged us closer and closer to the first aisle near the front door.

I’d never seen Dad move around like that, like a freaked-out squirrel. He looked scared and funny all at once, opening and closing doors. Suddenly, he disappeared. I stood on my tippy toes to see what he was up to.

Smash! A river of milk flowed out from the dairy section. It was followed by the noise of another broken bottle.

“What’s going on over there?” the storekeeper shouted as he came out from behind the till and went to investigate.

I was looking in the direction of the milk aisle, trying to catch a glimpse of Dad, but Josh pulled me close, yanked open my drawers, and stuffed in a few bags of chips, a handful of pepperettes, and a loaf of bread. I was shocked, food sticking halfway out of my waistband. Jerry was already at the door ten feet away, holding it open, his pants, too, bulging to the brim with goodies. Josh pulled my shirt and nudged me toward Jerry. I stumbled a few steps before Jerry grabbed my arm and walked me out the front door.

From the Ashes

From the Ashes